Dans cette partie, nous allons regarder un peu comment le droit de l’union peut s’appliquer à nos procédures brevets et comment celui-ci fonctionne.

Application du droit de l’union

Si la JUB est compétente

Si la JUB est compétente, le droit UE est directement applicable.

En effet, l’accord sur la JUB précise que la cour doit appliquer le droit de l’union (articles 20 et 24 de l’accord JUB).

Si la JUB n’est pas compétente

Si la JUB n’est pas compétente, le droit de l’union n’est normalement pas à prendre en considération car la CBE est une source de droit international et non un droit de l’union.

Pour autant, l’OEB peut tout à fait reconnaitre certains principes généraux de droit communs à tous les états membres (et comme grand nombre d’états membres sont également membres de l’union …) (D11/91).

Interprétation du droit de l’union

Se pose nécessairement la question de l’interprétation du droit de l’union.

En effet, il faut savoir plusieurs chose avant d’aller plus loin :

- la CJUE se réserve le droit exclusif d’effectuer cette interprétation car sinon des divergences d’interprétation surviendrait et homogénéité de l’application du droit serait remise en cause (Article 267 TFUE) ;

- seuls les tribunaux nationaux peuvent poser des questions préjudicielles d’interprétation (i.e. un tribunal international n’a pas cette capacité) (Article 267 TFUE).

Ainsi, afin de permettre aux cours de la JUB de pouvoir présenter des questions préjudicielles et ainsi appliquer correctement le droit de l’union, les différentes parties qui ont négociées la JUB ont astucieusement fait en sorte qu’une cour de la JUB soit en réalité un tribunal national (ou plus exactement, un tribunal commun de chaque pays membre, article 1 de l’accord JUB).

C’était d’ailleurs une obligation d’après l’avis de la CJUE sur l’ancêtre de la JUB (avis 1/09 du 8 mars 2011, CJUE).

Ce tribunal « commun » simplifie quand même beaucoup les choses en pratique, et notamment pour l’exécution des décisions : en effet, lorsque un tribunal de la JUB rend une décision, c’est une décision d’un tribunal français, mais aussi belge, mais aussi allemand, etc.

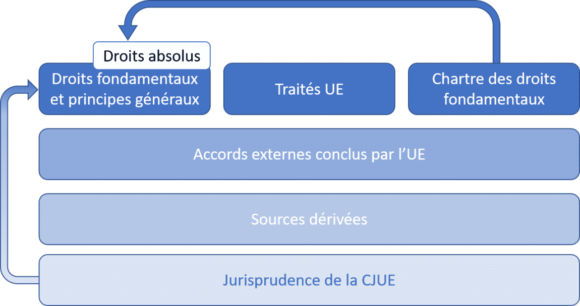

Sources du droit de l’union

Traités de l’union

L’union européenne est régie par de nombreux traités historiques, mais deux traités principaux peuvent être cités :

Sources dérivées

Le droit de l’Union européenne dérivé est composé des autres sources de droit de l’Union, définies dans l’article 288 TFUE :

- règlements, équivalent des lois nationales au niveau de l’Union : ils établissent des normes applicables directement dans chaque État.

- directives, au statut juridique original : destinées à tous les États ou parfois à certains d’entre eux, elles définissent des objectifs obligatoires mais laissent en principe les États libres sur les moyens à employer, dans un délai déterminé.

- décisions, obligatoires pour un nombre limité de destinataires.

- recommandations et avis, qui ne lient pas les États auxquels ils s’adressent. La Cour de justice de l’Union européenne estime toutefois qu’une recommandation peut servir à l’interprétation du droit national ou de l’Union.

Ce droit dérivé est, de loin, le droit le plus abondant.

Droits fondamentaux et principes généraux du droit de l’union

Il n’existe pas de liste fermée des droits fondamentaux et des principes généraux du droit de l’union mais nous pouvons citer :

- Droits fondamentaux

- le droit de propriété,

- la liberté d’exercer une activité professionnelle,

- l’inviolabilité du domicile ;

- la liberté d’opinion ;

- la protection de la famille ;

- la protection de la vie privée ;

- la liberté de religion et de croyance ;

- l’égalité de traitement,

- Principes généraux

- la suprématie du droit de l’union,

- le principe de subsidiarité,

- le respect des droits fondamentaux,

- le principe de la proportionnalité.

Parmi les droits fondamentaux, il faut noter un certain nombre de droits absolus (i.e. qui ne tolère pas d’exception) comme l’interdiction de la torture.

Bien entendu, pour qu’un principe soit reconnu comme principe général du droit de l’union, il faut un certain nombre d’indices et la simple mention d’un concept dans les traités ne suffit pas à le rendre général (ex. C-147/13 dans lequel l’Espagne soutenait que l’usage de toutes les langues de l’Union était un principe général et s’opposait donc à ce que les langues devant l’OEB se limite à trois langues officielles).

Charte des droit fondamentaux

Proclamée une première fois à Nice le 7 décembre 2000, puis officiellement adoptée dans sa version définitive par les présidents de la Commission européenne, du Parlement européen et du Conseil de l’UE le 12 décembre 2007, la Charte des droits fondamentaux a acquis une force juridique contraignante avec le traité de Lisbonne.

L’article 6 TUE prévoit en effet, en son premier paragraphe, que cette Charte a « la même valeur juridique que les traités ».

Concernant les droits de la PI, cette charte rappelle dans son article 17, que les droits de propriété intellectuelle doivent être protégés.

Accord externes conclus par l’UE

Les accords externes sont des conventions conclues entre, d’une part, l’UE avec ou sans ses Etats membres, et d’autre part, des pays tiers, groupements régionaux ou organisations internationales.

Par exemple, les accords conclus dans le cadre de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) sont des accords externes.

Jurisprudence de la CJUE

La jurisprudence comprend les arrêts des deux juridictions de la Cour de justice de l’Union européenne :

- la Cour de justice et

- le Tribunal.

Cette jurisprudence est particulièrement importante car elle permet d’assurer une interprétation unifiée des traités.

Bien entendu, cette jurisprudence définie à l’occasion les principes généraux du droit de l’union (vu précédemment) ainsi que les droits fondamentaux.

Hiérarchie des sources de droits

Afin de synthétiser la hiérarchie des sources de droits de l’union mentionnées précédemment, nous pouvons faire le graphique suivant :

Équilibre entre les différentes sources de droits

Introduction

Si deux sources de droit, de niveaux hiérarchiques différents, s’opposent, la source ayant la plus grande hiérarchie s’impose.

Cela est trivial, mais nous pouvons avoir plus de difficulté lorsque ces deux sources sont de même « niveau », par exemple :

- si le principe d’égalité de traitement s’oppose au principe de la propriété ;

- si le principe de la libre circulation s’oppose au principe de la santé publique.

Équilibre dans le domaine de la PI

Le domaine de la PI entraine un certain nombre de situations dans lesquelles les droits de PI viennent interférer avec des principes de l’union :

- droit de propriété ;

- droit à la vie privée (ex. système de filtrage, C-160/15, 8 septembre 2016, CJUE) ;

- liberté d’entreprendre (C-160/15, 8 septembre 2016, CJUE) ;

- liberté d’expression (ex. réutilisation d’une œuvre pour des fins politique ou commerciale, C-201/13, 3 septembre 2014, CJUE) ;

- etc.

Il faut donc trancher chaque situation en ayant en tête le principe de proportionnalité.

Principe de proportionnalité

Ce principe de proportionnalité est un principe général de l’union (Case 11/70, 17 décembre 1970 CJCE, maintenant codifié par Art 5.4 TUE et Art 52.1 de la Charte des droits fondamentaux).

Normalement, ce principe de proportionnalité devrait être appliqué en vérifiant un test à trois étapes :

- vérification que la loi est utile (i.e. elle atteint bien le but recherché) ;

- vérification que la loi est nécessaire (i.e. il n’existe pas d’autre moyen d’atteindre le but recherché, compte tenu de son impact) ;

- vérification que la loi est équilibrée avec le principe qu’elle remet en question.

Pour autant, il arrive que la CJUE soit plus souple et n’applique que les deux premiers tests (C-58/08 du 8 juin 2010, CJCE) ou uniquement le dernier test (C-70/10 du 24 novembre 2011, CJCE).

Il arrive même que la CJUE ne demande que le fait que la norme de l’union en question ne soit pas manifestement disproportionnée (C-331/88, CJCE).

Bref, ce principe de proportionnalité est bien souple 🙂